Down through history, governments have disarmed their citizens only to tyrannize those citizens once they were disarmed.

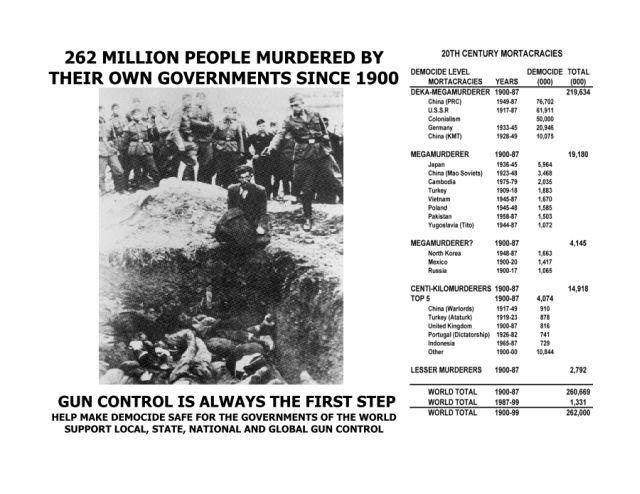

The following chart documents just a few examples from recent history where "gun control" laws were enacted and then tyranny by the government proceeded.

"GUN CONTROL" LAWS THAT HELPED SLAUGHTER 56 MILLION PEOPLE

| PERPETRATOR GOVERNMENT | DATE | TARGET | # MURDERED (ESTIMATED) | DATE OF GUN CONTROL LAW | SOURCE DOCUMENT |

| Ottoman Turkey | 1915-1917 | Armenians | 1-1.5 million | 1886-1911 | Art. 166, Penal Code Art. 166 Penal Code |

| Soviet Union* | 1929-1953 | Anti-Communists / Anti-Stalinists | 20 million | 1929 | Art. 182 Penal Code |

| Nazi Germany** & Occupied Europe | 1933-1945 | Jews, Gypsies, Anti-Nazis | 13 million | 1928-1938 | Law on Firearms & Ammunition, April 12 Weapons Law, March 18 |

| China* | 1949-1952 1957-1960 1966-1976 | Anti- Communists Rural Populations Pro-Reform Grou | 20 million | 1935-1957 | Arts. 186-7, Penal Code Art. 9, Security Law, Oct. 22 |

| Guatemala | 1960-1981 | Maya Indians | 100,000 | 1871-1964 | Decree 36, Nov 25 Decree 283, Oct 27 |

| Uganda | 1971-1979 | Christians Political Rivals | 300,000 | 1955-1970 | Firearms Ordinance Firearms Act |

| Cambodia | 1975-1979 | Educated Persons | 1 million | 1956 | Arts. 322-8, Penal Code |

* The law(s) mentioned are part of an older/or wider body of law on and regulation of private firearms ownership ** For a complete translation of these laws, including regulations specifically banning Jews from owning any weapons and a side-by-side comparison of the Nazi Weapons Law with the U.S. Gun Control Act of 1968, see "Gun Control": Gateway to Tyranny, J.E. Simkin & A. Zelman, 1992; available from JPFO

After the government of the Ottoman Empire quickly crushed an Armenian revolt in 1893, tens of thousands of Armenians were murdered by mobs armed and encouraged by the government. As anti-Armenian mobs were being armed, the government attempted to convince Armenians to surrender their guns. [4] A 1903 law banned the manufacture or import of gunpowder without government permission. [5] In 1910, manufacturing or importing weapons without government permission, as well as carrying weapons or ammunition without permission was forbidden. [6]

During World War I, in February 1915, local officials in each Armenian district were ordered to surrender quotas of firearms. When officials surrendered the required number, they were executed for conspiracy against the government. When officials could not surrender enough weapons from their community, the officials were executed for stockpiling weapons. Armenian homes were also searched, and firearms confiscated. Many of these mountain dwellers had kept arms despite prior government efforts to disarm them. [7]

The genocide against Armenians began with the April 24, 1915 announcement that Armenians would be deported to the interior. The announcement came while the Ottoman government was desperately afraid of an Allied attack that would turn Turkey's war against Russia into a two-front war. In fact, British troops landed at Gallipoli in western Turkey the next day. Although the Anglo-Russian offensives failed miserably, the Armenian genocide continued for the next two years. [8] Some of the genocide was accomplished by shooting or cutting down Armenian men. The bulk of the 1 to 1.5 million Armenian deaths, however, occurred during the forced marches to the interior. Although the marches were ostensibly for the purpose of protecting the Armenians through relocation, the actual purpose was to make the marches so difficult (for example, by not providing any food) that survival was impossible. [9]

The Armenian genocide differs from the six other genocides detailed in Lethal Laws in one important respect. Although many Armenians apparently complied with the gun control laws and the deportation orders, some did not. For example, in southern Syria (then part of the Ottoman Empire), "the Armenians refused to submit to the deportation order . . . . Retreating into the hills, they took up a strategic position and organized an impregnable defense. The Turks attacked and were repulsed with huge losses. They proceeded to lay siege." [10] Eventually 4,000 survivors of the siege were rescued by the British and French. [11] These Armenians who grabbed their guns and headed for the hills are the converse to the vast numbers of Armenian and other genocide victims in Lethal Laws who submitted quietly; although many of the Armenian fighters doubtless died from lack of medical care, starvation, or gunfire, so did many of the Armenians who submitted. As was the case of the Jewish resistance during World War II, armed resistance was enormously risky, but the resisters had a far higher survival rate than the submitters.

During World War I, in February 1915, local officials in each Armenian district were ordered to surrender quotas of firearms. When officials surrendered the required number, they were executed for conspiracy against the government. When officials could not surrender enough weapons from their community, the officials were executed for stockpiling weapons. Armenian homes were also searched, and firearms confiscated. Many of these mountain dwellers had kept arms despite prior government efforts to disarm them. [7]

The genocide against Armenians began with the April 24, 1915 announcement that Armenians would be deported to the interior. The announcement came while the Ottoman government was desperately afraid of an Allied attack that would turn Turkey's war against Russia into a two-front war. In fact, British troops landed at Gallipoli in western Turkey the next day. Although the Anglo-Russian offensives failed miserably, the Armenian genocide continued for the next two years. [8] Some of the genocide was accomplished by shooting or cutting down Armenian men. The bulk of the 1 to 1.5 million Armenian deaths, however, occurred during the forced marches to the interior. Although the marches were ostensibly for the purpose of protecting the Armenians through relocation, the actual purpose was to make the marches so difficult (for example, by not providing any food) that survival was impossible. [9]

The Armenian genocide differs from the six other genocides detailed in Lethal Laws in one important respect. Although many Armenians apparently complied with the gun control laws and the deportation orders, some did not. For example, in southern Syria (then part of the Ottoman Empire), "the Armenians refused to submit to the deportation order . . . . Retreating into the hills, they took up a strategic position and organized an impregnable defense. The Turks attacked and were repulsed with huge losses. They proceeded to lay siege." [10] Eventually 4,000 survivors of the siege were rescued by the British and French. [11] These Armenians who grabbed their guns and headed for the hills are the converse to the vast numbers of Armenian and other genocide victims in Lethal Laws who submitted quietly; although many of the Armenian fighters doubtless died from lack of medical care, starvation, or gunfire, so did many of the Armenians who submitted. As was the case of the Jewish resistance during World War II, armed resistance was enormously risky, but the resisters had a far higher survival rate than the submitters.

As the authors note, the Bolsheviks were a minority of Communists in a vast and disparate nation where Communists themselves were a tiny minority. It should not be surprising that the Bolsheviks worked hard to ensure that any person potentially hostile to them did not possess arms. [12]

The first Soviet gun controls were imposed during the Russian Civil War, as Czarists, Western troops, and national independence movements battled the central Red regime. Firearm registration was introduced on April 1, 1918. [13] On August 30, Fanny Kaplan supposedly wounded Lenin during an assassination attempt; the attempted assassination spurred a nationwide reign of terror. [14] In October 1918, the Council of People's Commissars (the government) ordered the surrender of all firearms, ammunition, and sabres. [15] As has been the case in almost every nation where firearms registration has been introduced, registration proved a prelude to confiscation. Exempt from the confiscation order, however, were members of the Communist Party. [16] A 1920 decree imposed a mandatory minimum penalty of six months in prison for (non-Communist) possession of a firearm, even where there was no criminal intent. [17]

After the Red victory in the Civil War, the firearms laws were consolidated in a Criminal Code, which provided that unauthorized possession of a firearm would be punishable by hard labor. [18] A 1925 law made unauthorized possession of a firearm punishable by three months of hard labor, plus a fine of 300 rubles (equal to about four months' wages for a highly-paid construction worker). [19]

Stalin apparently found little need to change the weapons control structure he had inherited. His only contributions were a 1935 law making illegal carrying of a knife punishable by five years in prison and a decree of that same year extending "all penalties, including death, down to twelve-year-old children." [20]

This chapter of Lethal Laws summarizes the genocide perpetrated by Stalin from 1929 to 1953, starting with his efforts to collectivize farming by destroying the class of property-owning farmers. Altogether, about twenty million people were murdered, worked to death in slave labor camps, or deliberately starved to death by Stalin's government. From 1929 to 1939, Stalin killed about ten million people, more than all the people who died during the entirety of World War I. Stalin's successful campaign of genocide against the Kulaks and against dissident Communists served as a model for similar campaigns in China and Cambodia. [21]

The first Soviet gun controls were imposed during the Russian Civil War, as Czarists, Western troops, and national independence movements battled the central Red regime. Firearm registration was introduced on April 1, 1918. [13] On August 30, Fanny Kaplan supposedly wounded Lenin during an assassination attempt; the attempted assassination spurred a nationwide reign of terror. [14] In October 1918, the Council of People's Commissars (the government) ordered the surrender of all firearms, ammunition, and sabres. [15] As has been the case in almost every nation where firearms registration has been introduced, registration proved a prelude to confiscation. Exempt from the confiscation order, however, were members of the Communist Party. [16] A 1920 decree imposed a mandatory minimum penalty of six months in prison for (non-Communist) possession of a firearm, even where there was no criminal intent. [17]

After the Red victory in the Civil War, the firearms laws were consolidated in a Criminal Code, which provided that unauthorized possession of a firearm would be punishable by hard labor. [18] A 1925 law made unauthorized possession of a firearm punishable by three months of hard labor, plus a fine of 300 rubles (equal to about four months' wages for a highly-paid construction worker). [19]

Stalin apparently found little need to change the weapons control structure he had inherited. His only contributions were a 1935 law making illegal carrying of a knife punishable by five years in prison and a decree of that same year extending "all penalties, including death, down to twelve-year-old children." [20]

This chapter of Lethal Laws summarizes the genocide perpetrated by Stalin from 1929 to 1953, starting with his efforts to collectivize farming by destroying the class of property-owning farmers. Altogether, about twenty million people were murdered, worked to death in slave labor camps, or deliberately starved to death by Stalin's government. From 1929 to 1939, Stalin killed about ten million people, more than all the people who died during the entirety of World War I. Stalin's successful campaign of genocide against the Kulaks and against dissident Communists served as a model for similar campaigns in China and Cambodia. [21]

German gun control laws are the authors' area of expertise. Mr. Simkin and Mr. Zelman have previously written a book analyzing the Weimar and Nazi gun laws in great detail. [22] The German chapter in Lethal Laws contains the most relevant statutes and regulations, but does not include gun registration forms and similar materials found in the previous book. Because Lethal Laws does contain more analysis of the German gun laws in their social context, Lethal Laws is the more valuable book to anyone except a specialist in German law.

After Germany's defeat in World War I, the democratic Weimar government, fearing (with good cause) efforts by Communists or the militaristic right to overthrow the government, ordered the surrender of all firearms. Governmental efforts to disarm the civilian population--in part to comply with the Versailles Treaty--apparently ended in 1921. [23]

The major German gun control law (which was not replaced by the Nazis until 1938) was enacted by a center-right government in 1928. [24] The law required a permit to acquire a gun or ammunition and a permit to carry a firearm. Firearm and ammunition dealers were required to obtain permits to sell and to keep a register of their sales. Also, persons who owned guns that did not have a serial number were ordered to have the dealer or manufacturer stamp a serial number on them. Permits to acquire guns and ammunition were to be granted only to persons of "undoubted reliability," [25] and carry permits were to be given "only if a demonstration of need is set forth." [26] Apparently police discretion cut very heavily against permit applicants. For example, in the town of Northeim, only nine hunting permits were issued to a population of 10,000 people. [27]

In 1931, amidst rising gang violence (the gangs being Nazi and Communist youths), carrying knives or truncheons in public was made illegal, except for persons who had firearm carry permits under the 1928 law. Acquisition of firearms and ammunition permits was made subject to proof of "need." [28]

When the Nazis took power in 1933, they apparently found that the 1928 gun control laws served their purposes; not until 1938 did the Nazis bother to replace the 1928 law. The leaving of the Weimar law in place cannot be attributed to lethargy on the Nazis' part; unlike some other totalitarian governments (such as the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia), the Nazis paid great attention to legal draftsmanship and issued a huge volume of laws and regulations. [29] The only immediate change the Nazis made to the gun laws was to bar the import of handguns. [30]

Shortly after the Nazis took power, they began house-to-house searches to discover firearms in the homes of suspected opponents. They claimed to find large numbers of weapons in the hands of subversives. [31] How many weapons the Nazis actually recovered may never be known. But as historian William Sheridan Allen pointed out in his study of the Nazi rise to power in one town: "Whether or not all the weapon discoveries reported in the local press were authentic is unimportant. The newspapers reported whatever they were told by the police, and what people believed was what was more important than what was true." [32]

Four days after Hitler's triumphant Anschluss of Austria in March 1938, the Nazis finally enacted their own firearms laws. Additional controls were layered on the 1928 Weimar law: Persons under eighteen were forbidden to buy firearms or ammunition; a special permit was introduced for handguns; Jews were barred from businesses involving firearms; Nazi officials were exempted from the firearms permit system; silencers were outlawed; twenty-two caliber cartridges with hollow points were banned; and firearms which could fold or break down "beyond the common limits of hunting and sporting activities" became illegal. [33]

On November 9, 1938 and into the next morning, the Nazis unleashed a nationwide race riot. Mobs inspired by the government attacked Jews in their homes, looted Jewish businesses, and burned synagogues, with no interference from the police. [34] The riot became known as "Kristallnacht" ("night of broken glass"). [35] On November 11, Hitler issued a decree forbidding Jews to possess firearms, knives, or truncheons under any circumstances, and to surrender them immediately. [36]

Nazi mass murders of Jews began after the invasion of the Soviet Union. Extermination camps were not set up until late 1941, so mass murder was at first accomplished by special S.S. units, Einsatzgruppen, on June 22, 1941. Working closely with regular army units, the Einsatzgruppen would move swiftly into newly-conquered areas, to prevent Jews from fleeing. In some cases, Jews were ordered to register with the authorities, an act which made them easy to locate for murder shortly thereafter. As noted above, most of the Soviet population had been disarmed by Lenin and Stalin or had never possessed arms in the first place. [37] Raul Hilberg, a leading scholar of the Nazi military, summarizes that

The killers were well armed, they knew what to do, and they worked swiftly. The victims were unarmed, bewildered, and followed orders. . . . It is significant that the Jews allowed themselves to be shot without resistance. In all reports of the Einsatzgruppen there were few references to "incidents." The killing units never lost a man during a shooting operation. . . . [T]he Jews remained paralyzed after their first brush with death and in spite of advance knowledge of their fate. [38]

How could Jews with "advance knowledge of their fate" allow themselves to be murdered? The authors suggest that

These Jews' passivity doubtless was the result of centuries of victimization in Russia. They had come to believe that being victimized was normal. In most cases in Jewish experience, the victimizers were satisfied after the first few victims. In such situations, resisting was likely to prolong the victimization, and thus to increase the number of victims. Most Jews did not realize that the Nazis were different. Most Jews did not realize the Nazis had no use for living Jews.

On top of this tendency to accept being victimized, twenty years of Communist rule--of which Stalin's terror had occupied ten years--had shown Jews that failure to obey orders was a fatal mistake. [39]

Although many Jews remained passive throughout the Holocaust, some did not. In 1943, the Nazis attempted to commence the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto. [40] But as the Nazis moved in, members of the Jewish Fighting Organization opened fire. "[T]he shock of encountering resistance evidently forced the Germans to discontinue their work in order to make more thorough preparations." [41] The revolt continued, leading Goebbels to note in his diary: "This just shows what you can expect from Jews if they lay hands on weapons." [42] Although the Jews of the Warsaw ghetto were eventually defeated, the Warsaw battle was perhaps the most significant ever for the Jews, according to Raul Hilberg: "In Jewish history, the battle is literally a revolution, for after two thousand years of a policy of submission the wheel had been turned and once again Jews were using force." [43]

There were other Jewish uprisings; even in the death camps of Sobibor and Treblinka, Jews seized arms from the Nazi guards and attempted to escape. A few succeeded, and more significantly, the camps were closed prematurely. [44] The authors do not attempt to tell the complete story of Jewish guerilla resistance during World War II. [45]

The German chapter is the most successful in the book. The perpetrators and the victims of Naziism both left extensive written records, allowing Simkin, Zelman, and Rice to integrate their always-strong textual analysis of the gun laws with a discussion of the actual impact of the laws on the lives of victims. [46]

After Germany's defeat in World War I, the democratic Weimar government, fearing (with good cause) efforts by Communists or the militaristic right to overthrow the government, ordered the surrender of all firearms. Governmental efforts to disarm the civilian population--in part to comply with the Versailles Treaty--apparently ended in 1921. [23]

The major German gun control law (which was not replaced by the Nazis until 1938) was enacted by a center-right government in 1928. [24] The law required a permit to acquire a gun or ammunition and a permit to carry a firearm. Firearm and ammunition dealers were required to obtain permits to sell and to keep a register of their sales. Also, persons who owned guns that did not have a serial number were ordered to have the dealer or manufacturer stamp a serial number on them. Permits to acquire guns and ammunition were to be granted only to persons of "undoubted reliability," [25] and carry permits were to be given "only if a demonstration of need is set forth." [26] Apparently police discretion cut very heavily against permit applicants. For example, in the town of Northeim, only nine hunting permits were issued to a population of 10,000 people. [27]

In 1931, amidst rising gang violence (the gangs being Nazi and Communist youths), carrying knives or truncheons in public was made illegal, except for persons who had firearm carry permits under the 1928 law. Acquisition of firearms and ammunition permits was made subject to proof of "need." [28]

When the Nazis took power in 1933, they apparently found that the 1928 gun control laws served their purposes; not until 1938 did the Nazis bother to replace the 1928 law. The leaving of the Weimar law in place cannot be attributed to lethargy on the Nazis' part; unlike some other totalitarian governments (such as the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia), the Nazis paid great attention to legal draftsmanship and issued a huge volume of laws and regulations. [29] The only immediate change the Nazis made to the gun laws was to bar the import of handguns. [30]

Shortly after the Nazis took power, they began house-to-house searches to discover firearms in the homes of suspected opponents. They claimed to find large numbers of weapons in the hands of subversives. [31] How many weapons the Nazis actually recovered may never be known. But as historian William Sheridan Allen pointed out in his study of the Nazi rise to power in one town: "Whether or not all the weapon discoveries reported in the local press were authentic is unimportant. The newspapers reported whatever they were told by the police, and what people believed was what was more important than what was true." [32]

Four days after Hitler's triumphant Anschluss of Austria in March 1938, the Nazis finally enacted their own firearms laws. Additional controls were layered on the 1928 Weimar law: Persons under eighteen were forbidden to buy firearms or ammunition; a special permit was introduced for handguns; Jews were barred from businesses involving firearms; Nazi officials were exempted from the firearms permit system; silencers were outlawed; twenty-two caliber cartridges with hollow points were banned; and firearms which could fold or break down "beyond the common limits of hunting and sporting activities" became illegal. [33]

On November 9, 1938 and into the next morning, the Nazis unleashed a nationwide race riot. Mobs inspired by the government attacked Jews in their homes, looted Jewish businesses, and burned synagogues, with no interference from the police. [34] The riot became known as "Kristallnacht" ("night of broken glass"). [35] On November 11, Hitler issued a decree forbidding Jews to possess firearms, knives, or truncheons under any circumstances, and to surrender them immediately. [36]

Nazi mass murders of Jews began after the invasion of the Soviet Union. Extermination camps were not set up until late 1941, so mass murder was at first accomplished by special S.S. units, Einsatzgruppen, on June 22, 1941. Working closely with regular army units, the Einsatzgruppen would move swiftly into newly-conquered areas, to prevent Jews from fleeing. In some cases, Jews were ordered to register with the authorities, an act which made them easy to locate for murder shortly thereafter. As noted above, most of the Soviet population had been disarmed by Lenin and Stalin or had never possessed arms in the first place. [37] Raul Hilberg, a leading scholar of the Nazi military, summarizes that

The killers were well armed, they knew what to do, and they worked swiftly. The victims were unarmed, bewildered, and followed orders. . . . It is significant that the Jews allowed themselves to be shot without resistance. In all reports of the Einsatzgruppen there were few references to "incidents." The killing units never lost a man during a shooting operation. . . . [T]he Jews remained paralyzed after their first brush with death and in spite of advance knowledge of their fate. [38]

How could Jews with "advance knowledge of their fate" allow themselves to be murdered? The authors suggest that

These Jews' passivity doubtless was the result of centuries of victimization in Russia. They had come to believe that being victimized was normal. In most cases in Jewish experience, the victimizers were satisfied after the first few victims. In such situations, resisting was likely to prolong the victimization, and thus to increase the number of victims. Most Jews did not realize that the Nazis were different. Most Jews did not realize the Nazis had no use for living Jews.

On top of this tendency to accept being victimized, twenty years of Communist rule--of which Stalin's terror had occupied ten years--had shown Jews that failure to obey orders was a fatal mistake. [39]

Although many Jews remained passive throughout the Holocaust, some did not. In 1943, the Nazis attempted to commence the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto. [40] But as the Nazis moved in, members of the Jewish Fighting Organization opened fire. "[T]he shock of encountering resistance evidently forced the Germans to discontinue their work in order to make more thorough preparations." [41] The revolt continued, leading Goebbels to note in his diary: "This just shows what you can expect from Jews if they lay hands on weapons." [42] Although the Jews of the Warsaw ghetto were eventually defeated, the Warsaw battle was perhaps the most significant ever for the Jews, according to Raul Hilberg: "In Jewish history, the battle is literally a revolution, for after two thousand years of a policy of submission the wheel had been turned and once again Jews were using force." [43]

There were other Jewish uprisings; even in the death camps of Sobibor and Treblinka, Jews seized arms from the Nazi guards and attempted to escape. A few succeeded, and more significantly, the camps were closed prematurely. [44] The authors do not attempt to tell the complete story of Jewish guerilla resistance during World War II. [45]

The German chapter is the most successful in the book. The perpetrators and the victims of Naziism both left extensive written records, allowing Simkin, Zelman, and Rice to integrate their always-strong textual analysis of the gun laws with a discussion of the actual impact of the laws on the lives of victims. [46]

The China chapter is much less enlightening, mostly because the victims of Mao's genocide, unlike Hitler's, left much less of a record for Western historians to uncover. While many scholars agree that about one million people were murdered during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), the number of people who were starved to death by Mao's communization of the economy from 1957 to 1960 ("the Great Leap Forward") might be as low as one million, or as high as thirty million. [47]

Mao, like Hitler, inherited gun control from his predecessor's regime. [48] A 1912 Chinese law made it illegal to import or possess rifles, cannons, or explosives without a permit. [49] The law was apparently aimed at the warlords who were contesting the central government's authority; Chinese peasants were far too poor to afford guns. [50] Communist gun control was not enacted until 1957, when the National People's Congress outlawed the manufacture, repair, purchase, or possession of any firearm or ammunition "in contravention of safety provisions." [51]

Mao, like Hitler, inherited gun control from his predecessor's regime. [48] A 1912 Chinese law made it illegal to import or possess rifles, cannons, or explosives without a permit. [49] The law was apparently aimed at the warlords who were contesting the central government's authority; Chinese peasants were far too poor to afford guns. [50] Communist gun control was not enacted until 1957, when the National People's Congress outlawed the manufacture, repair, purchase, or possession of any firearm or ammunition "in contravention of safety provisions." [51]

Perhaps the most overlooked genocide of the twentieth century has been the Guatemalan government's campaign against its Indian population. One reason that the genocide has attracted little attention may be that the Guatemalan government has been friendly to the United States.

Gun control in Guatemala has always been intimately tied to the military's determination to maintain itself as the dominant institution in society. [52] After taking power with a revolutionary army of just forty-five men, the Guatemalan government of 1871 speedily decreed the registration of all "new model" firearms. [53] Registered guns were subject to impoundment whenever the government thought necessary. [54] In 1873, firearms sales were prohibited, and firearms owners were required to turn their guns over to the government. [55]

Apparently, the enforcement of the 1873 law began to wane. In 1923, General Jose Orellana, who had taken power in a coup a few years before, put into force a comprehensive gun control decree. [56] The law barred most firearms imports, outlawed the carrying of guns in towns (except by government officials), required a license for carrying guns "on the public roads and railways," set the fee for a carry license high enough so as to be beyond the reach of poor people, and prohibited ownership of any gun that could fire a military caliber cartridge. [57]

In 1944, two officers led a revolt against the military government. [58] "Distributing arms to students and civilian supporters, they soon gained control of the city [Guatemala City, the capital], and two days later Ponce [the dictator] resigned, though not before nearly a hundred people had died in the sporadic fighting." [59] The first free elections in half a century were held. [60] The new government did not eliminate the gun control laws, but it did regularize the issuance of carry permits by specifying that the permits would be issued to an applicant who could "prove his good character by means of testimonials from two persons of known honesty." [61]

In 1952, the democratically-elected government of Jacobo Arbenz began an agrarian reform plan that expropriated large uncultivated estates. [62] Compensation was based on the taxable value of the land. The United Fruit Company was angry at the seizure of 386,000 acres of the company's reserve land in exchange for what the company considered inadequate compensation. [63] In June 1954, a force of Guatemalan exiles, trained by the CIA, invaded Guatemala from Honduras. [64] "Unable accurately to assess the situation in the capital, Arbenz resolved to do as he had done in 1944 and distribute weapons to the workers for the defense of the government. The army refused to obey, and on 27 June, Arbenz resigned . . . ." [65]

Contrary to the assertion of the authors, [66] it is unclear whether total repeal of the gun controls a decade before would have saved the democratic government. Firearms at a free-market price might still have been beyond the financial reach of the peasants and students in a very poor country. What might have made a difference, however, is the actual distribution of surplus military arms for free to the citizens of Guatemala while the democratic regime was in power. [67] But such a policy was not implemented, and for all practical purposes, the military retained a monopoly of force. As the authors note, the monopoly "made Arbenz, a duly elected President, serve at the Military's pleasure. When they wanted him to go, he went." [68]

In November 1960, reformist military officers attempted a coup and garnered the support of about half the army. [69] Peasants, wanting to fight for their own land, asked the rebels for guns so that the peasants could join the battle; the rebels refused. [70] The coup was finally crushed by loyalist forces who were supported by the United States. [71] From the 1960s to the 1980s, the Guatemalan government found itself engaged in perpetual counterinsurgency campaigns. As part of these campaigns, right-wing terror squads were unleashed to murder suspected subversives, although regular army units also participated extensively. [72] Approximately 100,000 Mayan Indians were murdered by the government during this period. [73]

Amnesty International has waged a long and courageous campaign against human rights abuses in Guatemala. [74] The authors reviewing Amnesty International's proposals for restoring human rights to Guatemala, note that the group nowhere advocates recognition of a strong legal right to arms or the arming of the victim populations. [75] Instead, Amnesty argues that the government should control itself better:

The government should also thoroughly review the present method of reporting and certifying violent deaths, particularly those resulting from actions taken by any person in an official capacity. The aim of such an inquiry should be to create procedures which will ensure that such deaths are reported to the authorities, who then impartially investigate the circumstances and causes of the deaths. All efforts should be made to identify the unidentified bodies that are found in the country and frequently buried only as "xx", in order to determine time, place and manner of death and whether a criminal act has been committed. [76]

Is the Amnesty proposal realistic? "It seems absurd," write Simkin, Zelman, and Rice, "to appeal to so blood-drenched a government to 'impartially investigate' atrocities its officials have committed." [77]

The failure of the Guatemalan government to prosecute its agents for perpetrating government-sponsored genocide suggests that hopes for domestic legal reform may be of little use in actually stopping genocide. As the next two chapters illustrate, international law may be of little greater practical efficacy.

Gun control in Guatemala has always been intimately tied to the military's determination to maintain itself as the dominant institution in society. [52] After taking power with a revolutionary army of just forty-five men, the Guatemalan government of 1871 speedily decreed the registration of all "new model" firearms. [53] Registered guns were subject to impoundment whenever the government thought necessary. [54] In 1873, firearms sales were prohibited, and firearms owners were required to turn their guns over to the government. [55]

Apparently, the enforcement of the 1873 law began to wane. In 1923, General Jose Orellana, who had taken power in a coup a few years before, put into force a comprehensive gun control decree. [56] The law barred most firearms imports, outlawed the carrying of guns in towns (except by government officials), required a license for carrying guns "on the public roads and railways," set the fee for a carry license high enough so as to be beyond the reach of poor people, and prohibited ownership of any gun that could fire a military caliber cartridge. [57]

In 1944, two officers led a revolt against the military government. [58] "Distributing arms to students and civilian supporters, they soon gained control of the city [Guatemala City, the capital], and two days later Ponce [the dictator] resigned, though not before nearly a hundred people had died in the sporadic fighting." [59] The first free elections in half a century were held. [60] The new government did not eliminate the gun control laws, but it did regularize the issuance of carry permits by specifying that the permits would be issued to an applicant who could "prove his good character by means of testimonials from two persons of known honesty." [61]

In 1952, the democratically-elected government of Jacobo Arbenz began an agrarian reform plan that expropriated large uncultivated estates. [62] Compensation was based on the taxable value of the land. The United Fruit Company was angry at the seizure of 386,000 acres of the company's reserve land in exchange for what the company considered inadequate compensation. [63] In June 1954, a force of Guatemalan exiles, trained by the CIA, invaded Guatemala from Honduras. [64] "Unable accurately to assess the situation in the capital, Arbenz resolved to do as he had done in 1944 and distribute weapons to the workers for the defense of the government. The army refused to obey, and on 27 June, Arbenz resigned . . . ." [65]

Contrary to the assertion of the authors, [66] it is unclear whether total repeal of the gun controls a decade before would have saved the democratic government. Firearms at a free-market price might still have been beyond the financial reach of the peasants and students in a very poor country. What might have made a difference, however, is the actual distribution of surplus military arms for free to the citizens of Guatemala while the democratic regime was in power. [67] But such a policy was not implemented, and for all practical purposes, the military retained a monopoly of force. As the authors note, the monopoly "made Arbenz, a duly elected President, serve at the Military's pleasure. When they wanted him to go, he went." [68]

In November 1960, reformist military officers attempted a coup and garnered the support of about half the army. [69] Peasants, wanting to fight for their own land, asked the rebels for guns so that the peasants could join the battle; the rebels refused. [70] The coup was finally crushed by loyalist forces who were supported by the United States. [71] From the 1960s to the 1980s, the Guatemalan government found itself engaged in perpetual counterinsurgency campaigns. As part of these campaigns, right-wing terror squads were unleashed to murder suspected subversives, although regular army units also participated extensively. [72] Approximately 100,000 Mayan Indians were murdered by the government during this period. [73]

Amnesty International has waged a long and courageous campaign against human rights abuses in Guatemala. [74] The authors reviewing Amnesty International's proposals for restoring human rights to Guatemala, note that the group nowhere advocates recognition of a strong legal right to arms or the arming of the victim populations. [75] Instead, Amnesty argues that the government should control itself better:

The government should also thoroughly review the present method of reporting and certifying violent deaths, particularly those resulting from actions taken by any person in an official capacity. The aim of such an inquiry should be to create procedures which will ensure that such deaths are reported to the authorities, who then impartially investigate the circumstances and causes of the deaths. All efforts should be made to identify the unidentified bodies that are found in the country and frequently buried only as "xx", in order to determine time, place and manner of death and whether a criminal act has been committed. [76]

Is the Amnesty proposal realistic? "It seems absurd," write Simkin, Zelman, and Rice, "to appeal to so blood-drenched a government to 'impartially investigate' atrocities its officials have committed." [77]

The failure of the Guatemalan government to prosecute its agents for perpetrating government-sponsored genocide suggests that hopes for domestic legal reform may be of little use in actually stopping genocide. As the next two chapters illustrate, international law may be of little greater practical efficacy.

Source:

http://www.mercyseat.net/gun_genocide.html

No comments:

Post a Comment